The Commonwealth Fund has long employed a dual approach to health care quality improvement: pursuing innovation in the delivery of care while, at the same time, comparing the effectiveness of prevailing approaches. Central to these efforts has been data — collecting it, analyzing it, and using it to drive health system transformation. As far back as the 1920s, when the Commonwealth Fund tracked changes in infant and maternal mortality rates following the rollout of its rural public health programs, the foundation has been assessing the impact of projects it supported. A commitment to improvement through evidence remains a hallmark of the Commonwealth Fund’s work.

Supporting New Models for Improving Health Care

Most Americans today are familiar with health maintenance organizations — HMOs. But in 1969, when the Harvard Community Health Plan (HCHP) began enrolling patients, HMOs were still highly experimental. In establishing the first HMO affiliated with a medical school and teaching hospital, HCHP’s founders were convinced that it is far less expensive to maintain health than it is to treat illness. They began with a single health care center in Boston; by the 1990s, there were 14 additional locations in the area as well as eight affiliated physician groups.

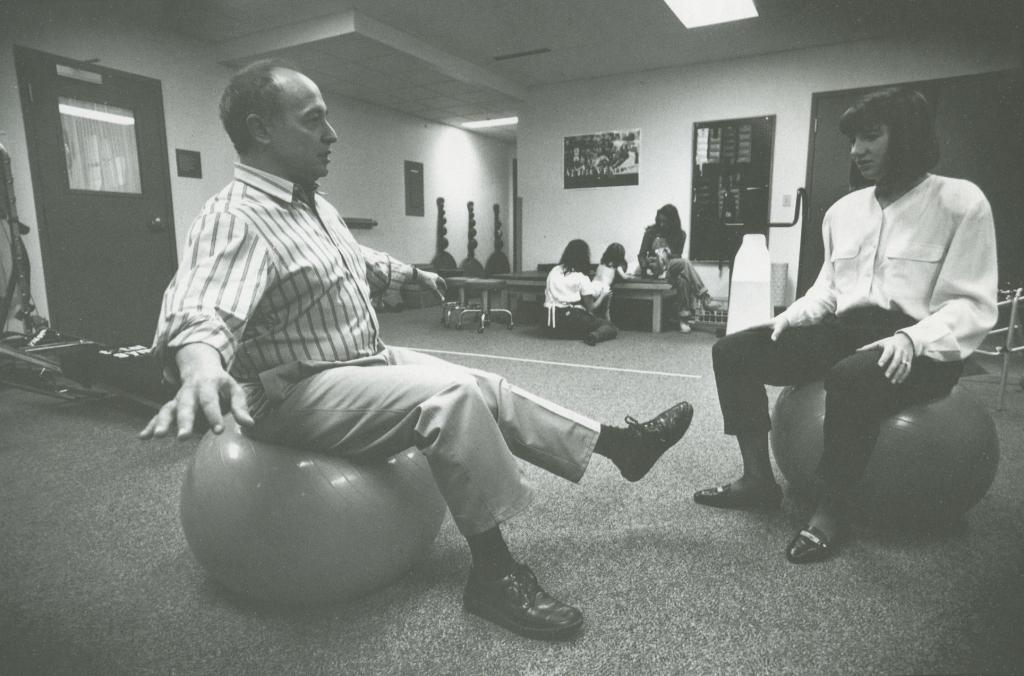

Photo: At Harvard Community Health Plan, created in 1969 with Commonwealth Fund support, physical therapy is part of a coordinated approach to patient care

The HCHP model, which received substantial Commonwealth Fund support, directly integrated a health insurance plan with a health care delivery system, built on a multispecialty medical group practice with links to hospitals, labs, and pharmacies. With their fee-for-service payments replaced by a fixed monthly payment per patient, physicians had incentive to keep people healthy and treat their medical problems efficiently. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, as it is known today, was rated first in member satisfaction and quality of care by the National Committee for Quality Assurance for nine consecutive years (2004–2012).

Increasing Quality of Care for the Most Vulnerable: The Elderly

Spurred to action by reports that more than a third of the nation’s elderly lived alone — many contending with poverty, chronic illness, or disability — the Commonwealth Fund made a grant in 1981 to future president Karen Davis entitled, “Meeting the Needs of the Functionally Dependent Elderly.” The project signaled a new programmatic interest, one that was to evolve by 1984 into the $1.6 million initiative Living at Home — A Nationwide Community Care Program for the Frail Elderly.

Photo: Elders Living Alone, 1992

The goal of the initiative was to keep the elderly out of nursing homes and in their homes and communities for as long as possible. The Commonwealth Fund and a consortium of other foundations provided financial incentives to hospitals that agreed to offer elders comprehensive in-home sociomedical care through cooperative agreements with apartment complexes. The following year, the five-year, $5 million Commonwealth Fund Commission on Elderly People Living Alone began its work to study ways of improving the economic, health, and social well-being of vulnerable seniors.

The foundation’s commitment to improving care for the elderly continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s, culminating in the Picker/Commonwealth Fund Program on Quality of Care for Frail Elders. Named for Jean and Harvey Picker, who in 1986 joined the James Picker Foundation’s $15 million in assets with those of the Commonwealth Fund, the program aimed to transform the nation’s nursing homes and long-term care facilities into organizations that prioritize improving quality of life for residents and creating a better working environment for the staff who care for them. Commonwealth Fund–supported evaluations of the resident-centered Green House and Wellspring Alliance models of long-term care demonstrated that “culture change” could achieve significant improvement in resident and staff well-being.

Later, in 2006, the Commonwealth Fund supported the launch of Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes, a national campaign to provide facilities with tools to make quality improvements and track their progress, compare their performance with peers, and learn about evidence-based practices. By 2012, more than half of all U.S. nursing homes had joined the campaign. Its work, now funded in part by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, continues to this day.

Benchmarking Performance

By the 2000s, the Commonwealth Fund had turned to assessing the performance of the U.S. health care system across multiple dimensions. Sheila Leatherman and Douglas McCarthy mined data from more than 150 published studies and reports for their groundbreaking series of chartbooks on quality of care in the U.S., which highlighted inadequate attention to preventive care, medical mistakes, and pronounced racial and geographic disparities in quality. Dana Safran and colleagues’ 2006 analysis of findings from the Massachusetts Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey not only demonstrated that patients’ health care experiences could be reliably measured using survey data, it illustrated the importance of focusing on how health care is delivered.

These studies and others helped lay the groundwork for the Commonwealth Fund’s series of health system scorecards, conceived by the Commission on a High Performance Health System (discussed below). The scorecards, which measure and rank how well health care systems at the state and local level serve people, have provided health care leaders, policymakers, and the media with a touchstone for benchmarking and comparing performance across the U.S. Since their inception, these resources — consistently among the Commonwealth Fund’s most highly used — have revealed persistent geographic, racial, and income-related disparities in care both within and between states. Recent scorecards, however, indicate states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility have made greater gains in access to care than states that have not.

In 2008 the Fund launched another health care benchmarking resource, WhyNotTheBest.org, designed to demonstrate that vetted, publicly available benchmarking and trend data could drive performance improvement in health care delivery. Featuring data on thousands of U.S. hospitals and health systems, case studies of top health care organizations, and an interactive map for exploring hospital performance by region, the website evolved over five years into a valued resource for quality improvement professionals, business health coalitions, and journalists. Since 2014, the national health care improvement organization IPRO has operated the site (wntb.org).

Providing National Leadership for the Health Care Debate

In 2005, the Commonwealth Fund’s leaders charged its new Commission on a High Performance Health System with envisioning a health care system that achieved improved coverage, quality, and efficiency. Focusing on the most vulnerable in society, including people with low income and members of racial and ethnic minorities, the group comprised 16 distinguished experts from the health care sector, the state and federal policy arenas, and business and academia. Their job was to track the effectiveness of health care in the U.S., develop policy options to improve health care, and propose innovative practice changes.

The commission’s influential 2007 report Bending the Curve: Options for Achieving Savings and Improving Value in U.S. Health Spending warned that the U.S. lacked a plan to tackle rising health costs. The authors presented 15 potential solutions — from accelerating providers’ adoption of health information technology to allowing Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices — that would lower spending while maintaining, or even enhancing, health care access, quality, efficiency, equity, and innovation. In 2009, The Path to a High Performance U.S. Health System outlined an integrated approach to improving health care. Its recommendations included the creation of a national insurance exchange offering a choice of private and public plans; a requirement that all Americans have health coverage; and insurance market reforms that promote the delivery of higher-value care. Many of these proposals are reflected in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Following the ACA’s passage in 2010, the commission focused on still-unresolved issues of access, equity, quality, and affordability. Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012, David Blumenthal, M.D., who succeeded James J. Mongan, M.D., as commission chair and is now the Commonwealth Fund’s president, explained that while “the national performance-improvement toolbox is now well stocked . . . the government needs a comprehensive, disciplined implementation plan that takes full, thoughtful advantage of its new opportunities.” He noted the importance of enabling clinicians and patients “to make better health care decisions by giving them the best available information where and when they need it and making it easy to do the right thing.”

Pursuing Promising Ways of Delivering and Paying for Care

Over the past decade, the Commonwealth Fund has supported projects gauging the potential of two new models to deliver comprehensive, high-quality care to people at lower costs. One of these models is the patient-centered care medical home (PCMH). Typically led by a primary care physician working with a multidisciplinary team of health professionals, the PCMH emphasizes ongoing care relationships, well-coordinated care, and the involvement of patients and family members in creating individualized care plans. Medical homes prioritize achieving the best possible outcomes for patients; the value of the care they receive, not the volume of services delivered, is paramount.

The Commonwealth Fund made important contributions to the PCMH movement in the 2000s, helping to create consensus around defining medical home principles and develop accreditation measures. Public and private health plans alike have used the implementation “toolkits” developed with Fund support to reorient care delivery along patient- and family-centered lines. The Commonwealth Fund has also supported numerous evaluations of medical home demonstrations. While results have been mixed, findings that indicate more appropriate utilization of health services and lower costs for high-risk patients suggest further inquiry is warranted.

More recently, the Commonwealth Fund has sponsored research into accountable care organizations (ACOs), networks of doctors, hospitals, and other care providers that assumes financial risk for treating a defined population of patients. As the name implies, ACOs are about accountability: they stand or fall based on their ability to produce good outcomes for their patients while keeping costs under control. Since 2009, the Fund has partnered with the Dartmouth Institute to understand how ACOs function, to evaluate their performance, and to investigate their impact on different groups of patients, including the chronically ill, patients with behavioral health and social service needs, and individuals with low income. An ACO pilot evaluation conducted jointly with Dartmouth showed modest cost savings for Medicare beneficiaries, with more significant gains seen for those with the highest needs. The Commonwealth Fund continues to study ACOs as the model continues to spread.

Improving Care for Patients with High Needs

A Commonwealth Fund survey conducted in 2016 found that the U.S. health care system is failing to meet the needs of patients with complex medical and social needs — a population that accounts for the largest portion of health spending across high-income nations. Although 95 percent of those surveyed had consistent access to health care, they nevertheless struggled to obtain the services they needed to stay well and avoid costly hospital visits, including assistance in managing functional limitations, emotional counseling, and transportation services.

The Better Care Playbook, an online resource developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement with funding from a five-foundation collaborative, outlines best practices in caring for these “high-need, high-cost” patients. By sorting information by the patient’s requirements and the user’s role within the health system, it helps connect providers with the most appropriate evidence-based interventions.

The Commonwealth Fund and its foundation partners continue to enhance the Better Care Playbook and more widely disseminate its tools and curricula for care redesign. Ultimately, the collaborative hopes to motivate and guide health care organizations, insurers, payers, and policymakers in improving care for this underserved population.