Since its founding in 1918, the Commonwealth Fund has sought to expand the availability of affordable, high-quality health care to all Americans. While the foundation’s tactics have shifted over time — from building medical facilities to piloting models of care to informing policy change — the commitment to this core value has never wavered.

Improving Physical Access to Services, Hospitals, and Medical Facilities

Rural Hospitals

When the Commonwealth Fund launched its Division of Rural Hospitals in 1926, more than half of U.S. counties, many of them rural and impoverished, had no hospital at all. The demonstration began as a partnership with six rural communities. The Fund covered the bulk of hospital building costs, while local officials procured the remainder and saw to ongoing maintenance.

“The story I had always heard was that [back in the 1920s], a group of people got together to see if a big city hospital would work in a rural community,” says Kerry Mossler, director of marketing and community affairs at Farmville, Virginia’s Centra Southside Community Hospital, which opened its doors in 1927 with support from the Commonwealth Fund and the local Lions Club. Southside, now part of the Centra Health System, is the only hospital in eight counties.

When the onset of the Great Depression temporarily halted new construction, the Commonwealth Fund continued to help the initial six hospitals improve their administrative operations and expand outpatient care.

Photo: A billboard supporting the passage of the Hill-Burton Act of 1946

In 1934, new construction resumed. But the Fund’s capacities were small relative to the nation’s overwhelming needs: nearly 800 hospitals had closed across the U.S. between 1928 and 1938, a period in which the U.S. population grew by nearly a million. In 1942, the Commonwealth Fund joined forces with the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to create the Commission on Hospital Care.

The Commission’s careful documenting of the inadequacy and haphazard distribution of hospitals across the country was crucial to passage of the seminal Hospital Survey and Construction Act of 1946. The legislation — better known as Hill-Burton, for its Senate sponsors Lister Hill of Alabama and Harold Burton of Ohio — called for the equitable disbursement of federal funds for hospital construction across the states.

“There was a feeling on all sides that hospitals would help small towns and rural areas develop a sense of community as well as be centers for health care,” noted Rosemary Stevens, a scholar in social medicine and public policy at Weill Cornell Medical College. “Hill-Burton was extremely successful in prodding movement in states for expanding hospital care. It funded nearly 4,700 projects in its first 20 years.”

The Commonwealth Fund closed its Division of Rural Hospitals in 1949, after supporting a total of 15 new hospitals across 13 states — and inspiring the creation of thousands more through Hill-Burton. Many of these institutions remain in operation today.

Rochester Regional Hospital Council

The Commonwealth Fund soon moved beyond building individual facilities to investigate whether joint planning and resource sharing could help small hospitals perform like their better-financed counterparts. In 1946, the foundation began just such an experiment in Western New York.

Operating in a seven-county region encompassing 4,700 square miles and 700,000 people, the new Rochester Regional Hospital Council was a partnership between six Rochester hospitals and 20 smaller area hospitals. In addition to defraying the costs of administering the network, the Commonwealth Fund’s $1.5 million in support from 1946 to 1954 helped pay for consultation services, a medical educational program, and health services. As Fund support wound down, member hospitals contributed a per-bed fee to sustain the effort.

While smaller rural hospitals were found to benefit the most, a review by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine determined that “the average quality of medical care available throughout the region improved rapidly.” Their review concluded that “this carefully developed and meticulously documented demonstration project laid the groundwork for what is now the norm in regional linkages connecting medical care providers.”

Ambulatory Care

The enrollment of millions of Americans in Medicare and Medicaid following the programs’ enactment in 1965 fueled increased demand for hospital services, along with a push to contain costs. While ambulatory care clinics presented a less expensive alternative to acute-care hospital units, at the time they were widely viewed as inferior “stepchildren” — typically staffed by trainee doctors using outdated technology.

But what if the quality of outpatient ambulatory care could be raised to the level of inpatient hospital care? In 1971, the Commonwealth Fund and the Carnegie Corporation of New York sought to find out. Together they funded Beth Israel Hospital of Boston, an affiliate of Harvard University Medical School, to construct a state-of-the-art ambulatory care center that would also serve as a laboratory for teaching, research, and experimentation.

Tom Delbanco, M.D., founding chief of the Division of General Medicine and Primary Care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, arrived at the hospital that year with a mission to attract young health professionals to careers in primary care. “Beth Israel Ambulatory Care soon attracted national attention, as teams of faculty physicians, nurses, and mental health professionals offered ‘one-stop shopping’ to patients of widely disparate backgrounds.”

In 1975, the Commonwealth Fund, W. K. Kellogg Foundation, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation jointly supported the continued development of teaching and research at the ambulatory care center, which today is an exemplar for the delivery of cost-effective hospital outpatient care.

Enhancing the Medical Professions

Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

In the 1960s, an acute shortage of physicians was limiting access to primary care services in rural and inner-city areas of the U.S. Believing that public health nurses could be trained to take on many aspects of routine pediatric care, the Commonwealth Fund supported the nation’s first nurse practitioner education program, launched at the University of Colorado Medical School in 1966.

“Our nurse practitioner program was founded by Loretta Ford, whose experience as a military and rural public health nurse convinced her that nurses could assume an expanded role in patient care,” says Mary Krugman, Ph.D., R.N., interim dean at the University of Colorado’s nursing program. “Today, nurse practitioners are critical to our rural communities.”

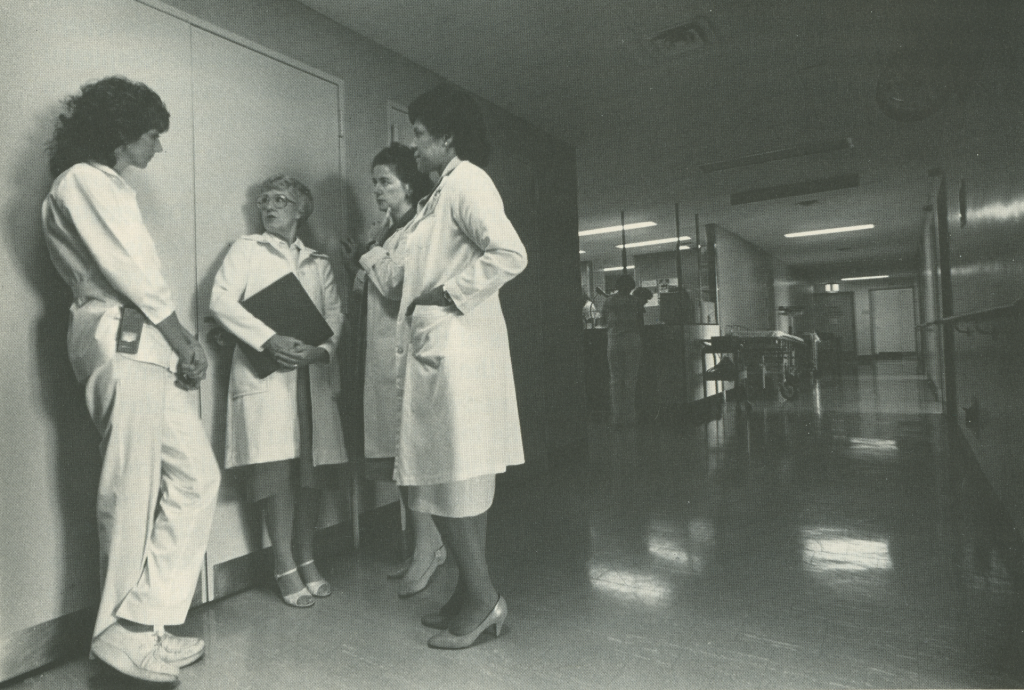

Photo: Loretta C. Ford, R.N., EdD., founder of the Commonwealth Fund-supported University of Colorado nurse practitioner training program, and later dean and director of nursing at the University of Rochester, pictured in 1984 explaining the Commonwealth Fund's Executive Nurse Leadership Program to prospective candidates

Graduates of the original class went on to establish nurse practitioner training programs across America.

Two years later, in 1968, the Commonwealth Fund began sponsorship of the Duke University School of Medicine’s Department of Community Health Sciences, which had been exploring a new category of health care worker: the physician assistant. Conceived as a professional with some background in health – gained through military service, for example – the physician assistant would be trained to handle routine but time-consuming tasks, such as taking medical histories and conducting diagnostic tests. The next year, Duke began sending graduates to rural and inner-city communities to deliver primary care as part of a pilot training program supported by the Commonwealth Fund, the Carnegie Corporation, and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Our nurse practitioner program was founded by Loretta Ford, whose experience as a military and rural public health nurse convinced her that nurses could assume an expanded role in patient care. Today, nurse practitioners are critical to our rural communities.

The 1971 Comprehensive Health Manpower Training Act, which included a focus on educating and training nurse practitioners and physician assistants, codified the important roles of these professionals in the nation’s health care system.

Measuring Access to Care and Identifying Gaps in Coverage

By the start of the 21st century, the Commonwealth Fund’s efforts on health care access centered on tracking and analyzing trends in Americans’ ability to get the care they need. The Fund also began informing the development of reforms to extend affordable insurance coverage to as many people as possible.

The Biennial Health Insurance Survey

Conducted every other year since 2001, the Commonwealth Fund’s Biennial Health Insurance Survey has served as the backbone of the foundation’s work on health coverage and access to care in America. Responses from the nationally representative survey of U.S. adults have allowed Fund analysts and other researchers to track trends in coverage rates, continuity of coverage, problems obtaining care because of costs, and difficulty paying medical bills and managing medical debt. In addition, the survey is unique in examining “underinsurance” — the inadequate protection from high health care costs that can result from poorly designed coverage.

The 2014 biennial survey provided one of the first broad-based assessments of changes in Americans’ health coverage after implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s insurance expansions. Its findings showed, for example, dramatic improvements in Americans’ health coverage since the law’s 2010 passage.

The most recent survey, conducted in 2016, found that 12 percent of U.S. adults are uninsured, down from 20 percent in 2010, and that young adults have made the greatest gains in coverage of any age group. Some discoveries were troubling: Hispanics are twice as likely as African Americans or whites to lack a consistent health care provider, and poorer Americans are far more likely to skip important preventive services.

Monitoring the Affordable Care Act

It can take years for the federal government to collect enough data to meaningfully assess the impact of policy reforms. This makes the research of the Commonwealth Fund and other private organizations especially important in the early period following a new law’s implementation. In 2013, the Fund began the Affordable Care Act Tracking Surveys, designed to track the implementation and impact of the ACA — the most significant reform of health care in the U.S. since the launch of Medicare and Medicaid.

Our ongoing health coverage surveys are part of a continuum of Commonwealth Fund efforts stretching back decades to identify gaps in Americans’ health care and point to practical ways of filling those gaps.

The ACA Tracking Surveys have provided policymakers and the media with timely information on changes in insurance coverage and affordability, public awareness of the law’s coverage provisions, and consumers’ experiences shopping in the health insurance marketplaces or enrolling in Medicaid. Survey questions also provide insights into people’s satisfaction with their new coverage and how they are using benefits to obtain health care.

The findings, presented in widely cited reports, blog posts, and social media channels, have not only provided federal authorities with a gauge of the law’s performance but also informed the development of policy options to improve it.

“Our ongoing health coverage surveys are part of a continuum of Commonwealth Fund efforts stretching back decades to identify gaps in Americans’ health care and point to practical ways of filling those gaps,” said Vice President Sara Collins, who heads the Fund’s Health Care Coverage and Access Program. “But while we’re proud of our role in informing the nation’s most recent health reform push, we’re also keenly aware that the nation must work to hold the ground that’s been gained so far and keep working until everyone is covered.”

In an era of controversy about the role that government should play in health care, Commonwealth Fund surveys and analyses have helped to ground public debate in objective evidence — to use research to produce facts that can speak for themselves. It’s a principle that has served the foundation well since the beginning, and one that is certain to guide it well into the future.