Photo: Former Commonwealth Fund President Margaret Mahoney meets with Harkness Fellows in 1984

From the start, the Commonwealth Fund has understood the value of engaging internationally. What began as aid for war-ravaged regions in Europe and Asia after World War I soon evolved into a novel approach to philanthropy, built on the notion that the United States and its peer nations stand to learn a lot from one other. Over the decades, the Commonwealth Fund has assumed a unique role as facilitator of cross-national exchange and learning on a range of health care issues.

Early International Health Care Efforts

The Commonwealth Fund’s earliest international forays took the form of direct assistance for Armenian and Syrian populations under siege during World War I. Following the war, Fund support to the American Relief Administration, whose budget was a mix of federal dollars and private donations, provided food and clothing to Austria, whose population was one of many in Europe suffering from the war’s devastation.

Sometime during the Austrian relief effort, however, the Commonwealth Fund’s leaders realized that a higher-impact, longer-lasting solution lay in capacity building. As explained in the Commonwealth Fund’s 1923 annual report, “[There is] an imperative need, now that the emergency has to some extent passed, of intelligent provision for the health of Austria’s children.”

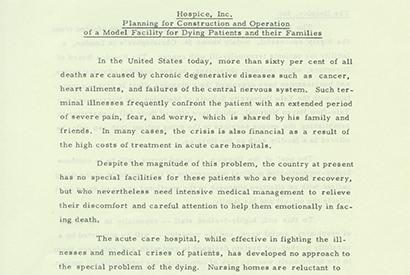

Photo: Map of Commonwealth Fund-supported child health activities in Austria circa 1925

From 1924 to 1929, the Commonwealth Fund embarked on a full-scale child health program in Austria. Expanding on the clinics for infants and children that the Red Cross had established during the war, the program centered on support for child health stations, hospitals and convalescent homes, and training for midwives and other health personnel. Notably, neither the Fund nor its grantees attempted to impose American views on health; the goal, rather, was to help Austrians develop the infrastructure for their own health system.

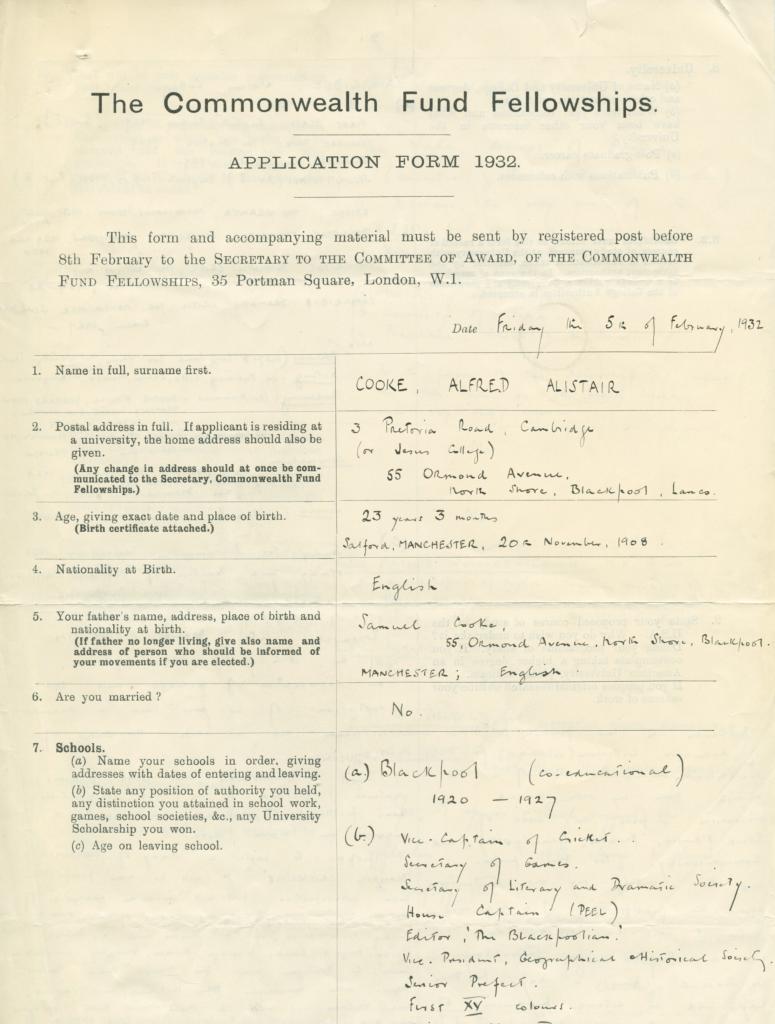

The Commonwealth Fellowships program, established in 1925 and later renamed the Harkness Fellowships, is one of the foundation’s most enduring and best-known enterprises. Initially granted to citizens of British Commonwealth nations for study and travel in the United States, the fellowships were eventually expanded to other countries. For nearly 75 years, fellows hailed from a variety of fields: literature, art history, political science, and health care, among many others. The program’s alumni included many of the 20th century’s most famous figures, from theoretical physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson to journalist and broadcaster Alistair Cooke.

Photo: British journalist Alistair Cooke's 1932 Harkness Fellow application

“I gained an enormous amount from my experiences as a Harkness Fellow — not only a deeper knowledge of public health issues but also a brilliant network of friends and professionals,” said Simon Stevens, the current chief executive of NHS England and a Harkness Fellow in the mid-1990s. “The opportunity to work internationally helps you differentiate between the distinctive things in your own country that really must be preserved and the things that, frankly, you could do better.”

In 1997, the Commonwealth Fund began to focus the Harkness Fellowships solely on health care policy and practice, thereby aligning the program fully with the foundation’s mission. Since that time, the program has produced a global cadre of some 250 health care professionals from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Fellows gain an in-depth knowledge of the U.S. health system during their study, helping to inform their thinking about pressing policy and care delivery issues in their own countries. Alumni make ongoing contributions to health care improvement efforts in the U.S. as well. Recently, former Harkness Fellows have helped the Commonwealth Fund identify effective models of health care delivery from abroad that could potentially be transferred to health systems in the U.S.

The opportunity to work internationally helps you differentiate between the distinctive things in your own country that really must be preserved and the things that, frankly, you could do better.

“In addition to the important contributions to health care delivery and policy that returning Harkness Fellows have made in their home countries, the program has produced enormous dividends for the Commonwealth Fund itself,” noted Robin Osborn, the Fund’s vice president for international health policy and practice innovations. “The expertise and firsthand knowledge the fellows bring from their countries have allowed us to look at the U.S. health system through a different lens. Their insights are a big reason why the Fund is a leader in comparative information on health system performance internationally.”

Importing a New Concept of Care

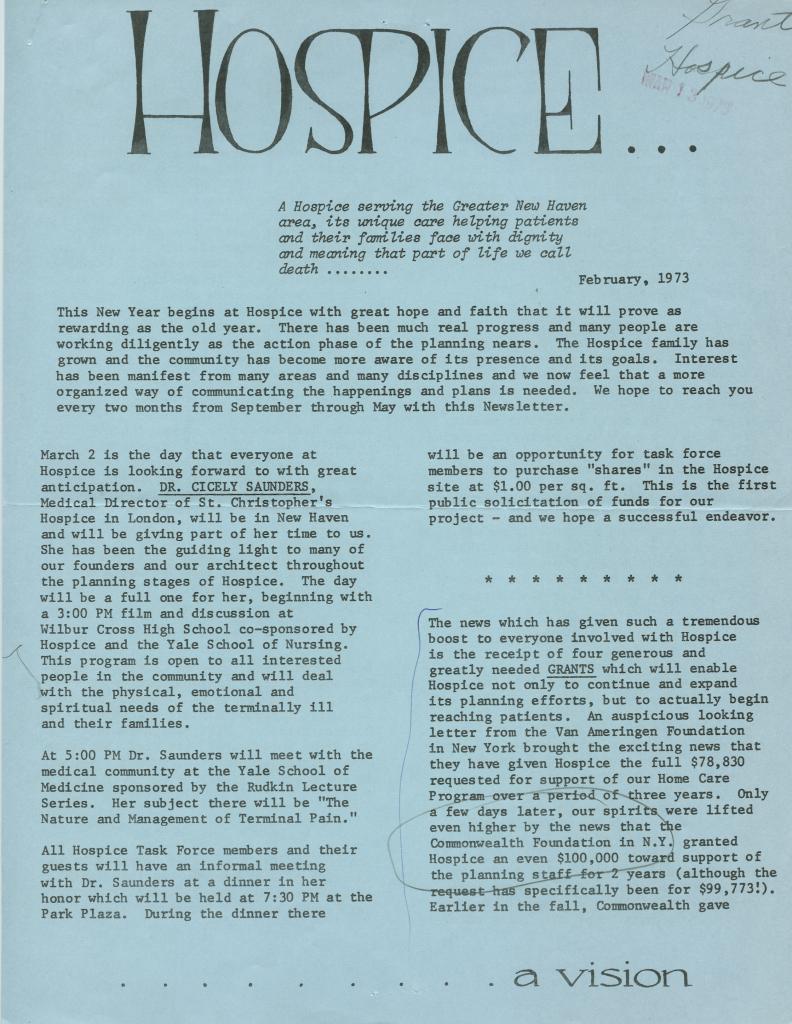

In 1974, the Commonwealth Fund supported the establishment of the first hospice in the U.S. It was the culmination of an effort that began when Florence Wald, dean of the Yale School of Nursing, organized a two-year study group to examine American society’s attitudes toward the terminally ill.

The hospice concept had had a long history throughout Europe, emerging from medieval traditions of caring for travelers. But the “places of comfort” for the dying that had evolved by the 19th century were not medically sophisticated. By the 1930s, these facilities had largely been replaced by hospital and nursing home care.

Photo: A 1973 Hospice Inc., newsletter

When St. Christopher’s Hospice opened in London in 1967, it offered a modern model of terminal care that combined inpatient services, home care, and bereavement support. Its focus on humane dying, however, was new and somewhat controversial, making philanthropic backing all the more crucial to the model’s eventual spread to the U.S.

Commonwealth Fund support, along with funding from the Van Ameringen Foundation and the Ittleson Family Fund, was indeed critical to the opening of Hospice, Inc., in Branford, Connecticut, in 1974. Modeled on St. Christopher’s and planned in conjunction with the Yale University Schools of Medicine and Nursing and Yale-New Haven Hospital, what is today known as The Connecticut Hospice featured a staff of professionals trained in psychiatry, social work, and ministry.

The Commonwealth Fund supported a feasibility study, provided initial staff support, and funded the initiative’s two-year planning and fundraising phase. It also helped the hospice founders secure a $1.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute.

The Fund not only shined a light on the need for a new model of care for terminally ill individuals but also attracted the broad-based support necessary for the hospice movement to take hold across the U.S.

Providing International Metrics for Policymakers

For nearly two decades, the Commonwealth Fund has conducted annual surveys in Europe and North America to find out how the health care systems of high-income countries compare to one another. Starting with five countries in 1998 and expanding to 11 by 2017, the surveys interviewed alternating samples of patients, clinicians, hospital executives, and the public about topics such as financial barriers to care, chronic disease management, satisfaction with care, and provider capacity.

By allowing for valid international comparisons, the surveys illuminate for policymakers, health care leaders, researchers, and consumers how differences in national approaches to health care can affect everything from patients’ access to treatment to how much a nation spends on insurance coverage and care. For example, in the U.S., which lacks universal coverage, the surveys have repeatedly shown that Americans forgo health care because of cost more often than residents of other nations. They also face higher medical bills and spend more time resolving issues with their insurance companies.

We should adapt what works in other countries and build on our own strengths to achieve a health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.

Public dissemination of the Commonwealth Fund survey findings has also spurred actions to address shortcomings in health system performance in participating countries. In the U.K., patients’ reports of limited involvement in managing their care helped prompt implementation of national standards for individual care plans for the chronically ill. In New Zealand, a reduction in cost-sharing burdens for patients with low income came about partly in response to evidence from early surveys showing that the poor faced high financial barriers to primary care. And in Sweden, where health policy is made primarily at the county level, the health ministry presents survey findings to local officials across the country to inform their decisions.

The survey results also inform the Commonwealth Fund’s health system rankings for selected countries that have been published regularly since 2004. The 2017 rankings had the U.K. first overall — and the U.S. last — among the 11 countries included in the study, which examined performance on measures of health system equity, access, administrative efficiency, care delivery, and patient outcomes.

“Far too many people in the U.S. can’t afford the care they need, and far too many are uninsured, especially compared to other wealthy nations,” noted the Commonwealth Fund’s Eric C. Schneider, M.D., at the time of the report’s release. “We should adapt what works in other countries and build on our own strengths to achieve a health system that provides affordable, high-quality care for everyone.”