From the beginning, a hallmark of Commonwealth Fund philanthropy has been a commitment to addressing inequities in health and health care in the United States. The foundation’s early efforts included programs to prevent juvenile delinquency and expand infant and maternal health care. More recent projects have sought to increase minority representation in care delivery and health policy. Underpinning all this work has been the recognition that the achievement of any meaningful reduction in entrenched disparities requires a commitment to dealing with their root causes.

Improving Health Care for Women

In its 2010 report Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) observed that even though women are slightly more than half the U.S. population, their health needs “have lagged in medical research.” A key reason, the report noted, is that women are too often viewed as “a special, minority population.”

The Pap Smear: From "Highly Speculative" to Routine

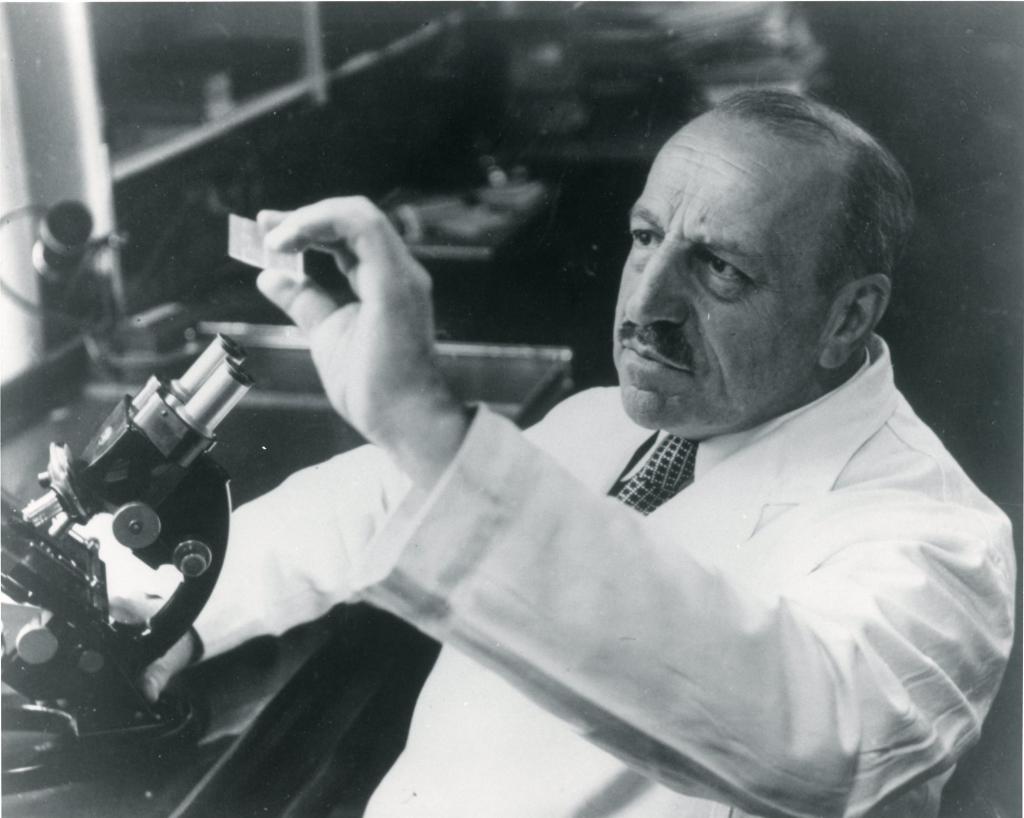

In 1928, George Papanicolaou, a physician at Cornell Medical College, became convinced that observing vaginal smear samples under a microscope enabled him to differentiate between normal and cancerous cells — a claim disputed by the prevailing medical establishment. Though cervical cancer was, at the time, the deadliest cancer among women, pathologists argued that the slower biopsy process was sufficient. Discouraged, Papanicolaou dropped his cancer research to focus on other fields.

Photo: George Papanicolaou, at Cornell Medical College

A decade later, however, he returned to the study of cellular irregularities. His techniques had still not won acceptance, and traditional funders of cancer research, including the American Cancer Society, declined his requests. But, in 1941, the Commonwealth Fund took a chance on Papanicolaou, offering him a $1,800 research grant that, according to an internal memo, was “highly speculative.”

It was then, at a moment when every hope had almost vanished, that the Commonwealth Fund, a society not primarily devoted to cancer research, stepped in. What appeared to be a speculative project 11 years ago is now a recognized and well-founded contribution to the biological and medical sciences.

With the foundation’s support, Papanicolaou could now examine a far greater number of sample smears, enabling him to prove beyond doubt that exfoliative cytology revealed irregularities in cells even before they turned cancerous. In 1943, the Commonwealth Fund published his groundbreaking work Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Smear.

Today, the Pap smear, as the test is now known, is a routine part of gynecological checkups. By cutting death rates from cervical cancer in half, the Pap smear has saved the lives of millions of women worldwide.

The Commonwealth Fund provided George Papanicolaou with more than $120,000 in support between 1941 and 1951 for his pioneering research.

“It was then, at a moment when every hope had almost vanished, that the Commonwealth Fund, a society not primarily devoted to cancer research, stepped in,” wrote Papanicolaou in 1953. “What appeared to be a speculative project 11 years ago is now a recognized and well-founded contribution to the biological and medical sciences.”

Commission on Women's Health

The Pap smear’s backstory is but one illustration of how medicine, and society at large, can marginalize women’s health. Seeking to “address serious and neglected problems in women’s health,” the Commonwealth Fund in 1993 launched the three-year, $4 million Women’s Health Program. That same year, the Fund established the Commission on Women’s Health to help guide the program’s work. Chaired by Ellen Futter, then president of Barnard College, the commission counted among its members Mary Mundinger, the former longtime dean of Columbia University’s School of Nursing, and Judy Woodruff, currently the anchor and managing editor of the PBS NewsHour.

Photo: Former Commonwealth Fund President Karen Davis presents results of the Survey of Women’s Health in 1994

It was exciting to see a growing understanding among women of their health issues as deserving of attention apart from those of men and children.

The five-year commission spotlighted women’s health issues and explored ways to improve access to health care services, improve mental health treatment, tackle violence and abuse, and address the health needs of adolescent girls. Findings from the commission’s population surveys and studies, which garnered significant media attention, highlighted rising uninsured rates among women during the 1990s. They helped to reframe domestic violence as a public health concern. And they revealed that, while women were becoming better informed and leading healthier lives than in previous decades, these gains were confined largely to the affluent and educated.

“It was exciting to see a growing understanding among women of their health issues as deserving of attention apart from those of men and children,” reflected Joan M. Leiman, the commission’s executive director. “There was increased attention to these issues from the press, from public figures, and from physicians and medical associations. It had the feel of a revolution — a culture change in the way women’s health and health care was approached.”

Child Development and Early Intervention

The Commonwealth Fund was born during a time of growing concern about child health and welfare. A third of American men drafted during World War I had been found unfit to serve, many for reasons linked to childhood neglect. The few health services that had been established for children were chronically understaffed and underfunded, and too often focused on disease response rather than prevention.

“Child health specialists agree that they possess the knowledge of what to do and how to do it,” said Barry C. Smith, who served as general director of the Commonwealth Fund for most its first three decades. “Nowhere, however, has a complete program been carried out.”

Child Health Demonstration Program

The Commonwealth Fund’s Child Health Demonstration, carried out from 1922 to 1929, sought to test whether a combination of preventive services, coordinated care, sanitation improvements, and health education could improve the lives of children. The foundation selected four communities for the demonstration: Fargo, North Dakota; Athens, Georgia; Rutherford County, Tennessee; and Marion County, Oregon.

Aiming to reach all children in each study area, the program required robust communication among schools, health departments, and private physicians. An administrative director organized services and formed partnerships with each community, while a full-time pediatrician, supported by a large nursing staff, led a medical service.

The program achieved notable results, including precipitous drops in infant and maternal mortality rates. In fact, the demonstrations were found sufficiently successful and cost-effective that all four communities voluntarily maintained the established services once the demonstration ended, even after the Great Depression took hold.

Child Guidance

In that same decade, the field of child guidance — a term coined by the Commonwealth Fund — emerged as a preventive approach to juvenile delinquency, perceived as a widespread problem at the time. From 1922 to 1927, the Fund piloted eight child guidance clinics across the U.S. Care teams of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers tested children for mental, emotional, or behavioral problems; examined their home environments; and created tailored treatment plans. Clinics worked with local juvenile courts, schools, and children’s agencies to identify those deemed “predelinquent” — often impoverished children with chaotic home lives.

Seven of the original eight child guidance clinics continued after the demonstration period ended in 1927. Within a decade, 230 clinics had been established across the U.S.

The Commonwealth Fund’s early emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention helped lay the groundwork for future publicly funded initiatives such as the Early and Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program, created in the 1960s to ensure that low-income families received needed comprehensive developmental services, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which has provided insurance coverage for poor and near-poor children since the 1990s.

Healthy Steps for Young Children

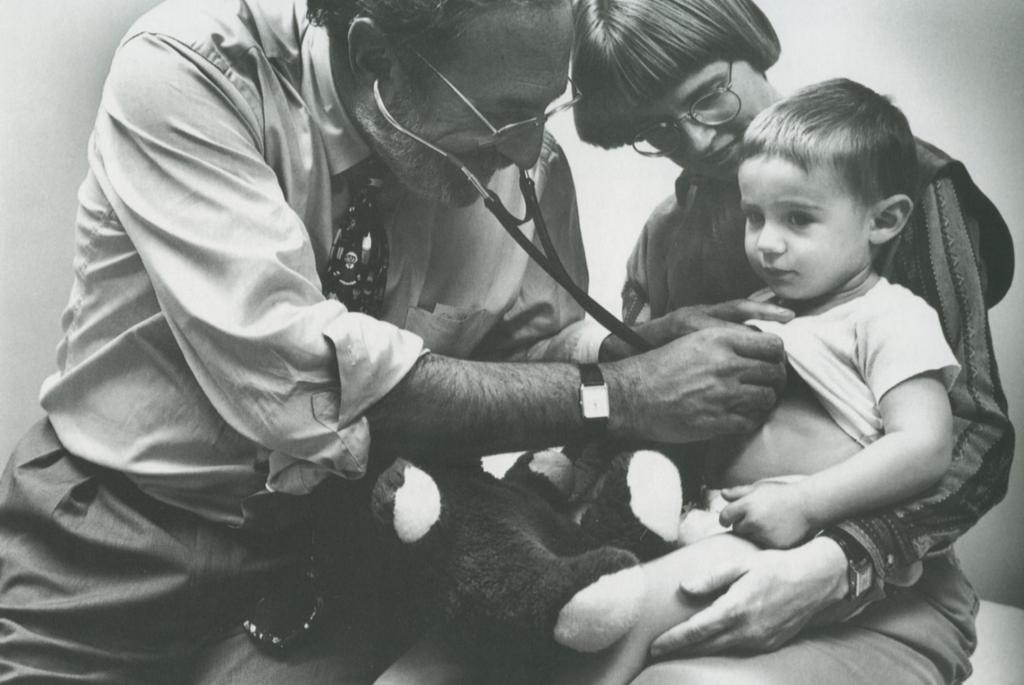

Photo: Dr. Barry Zuckerman of Boston University School of Medicine led a multidisciplinary pediatric research team for the Fund’s Health Steps for Young Children Initiative, beginning in 1994

The Commonwealth Fund’s interest in early child development reemerged later in the 20th century with Healthy Steps for Young Children, a model of enhanced preventive care championed by Margaret Mahoney, the foundation’s president from 1980 to 1995. Created to support children’s growth and well-being from birth to age 3, the $4.5 million demonstration’s most distinctive feature was embedding a child development specialist — whether a nurse, nurse practitioner, social worker, or early childhood educator — in participating pediatric care practices. The Healthy Steps Specialist monitored children’s development, attended closely to growth-related issues, and responded to parental concerns through a menu of services such as home visits, telephone support, and support groups.

As reported in the Journal of Urban Health, Healthy Steps began to “narrow the income gaps in utilization of preventive-health services, timely well-child care, and satisfaction with care for families with young children.” While the Commonwealth Fund no longer supports Healthy Steps, the program continues to this day.

The ABCD Initiative

In 1996, the Commonwealth Fund’s Survey of Parents with Young Children found that pediatricians were missing opportunities to encourage healthy practices in parents of infants and toddlers, detect and treat maternal depression, and provide information and services that would help parents navigate early childhood development. Two years later, shortly after the passage of CHIP, the Commonwealth Fund launched an initiative called ABCD — Assuring Better Child Health and Development —to help ensure that low-income families with young children received crucial surveillance, screening, assessment services, parenting tools and information, and care coordination services.

Working in partnership with the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), the Commonwealth Fund identified four states both eager to participate and willing to raise the necessary matching funds: Utah, Vermont, North Carolina, and Washington. Each had stable, committed Medicaid agency staff as well as a strong track record of statewide collaboration among stakeholders. All states were required to provide a detailed outcomes plan and to participate in a cross-state “think tank” that aimed to seed innovation and promote the spread of best practices.

The ABCD Initiative achieved impressive results following its launch in 2000. In all four states, EPSDT screenings markedly increased; in North Carolina, the rate jumped from 15 percent to 70 percent within one year.

For the program’s second phase, five new states were chosen from among 25 applicants to participate in a laboratory for testing additional ways to expand and improve developmental services for at-risk children. Between 2003 and 2010, the proportion of children under age 3 served by the states’ early-intervention programs increased 22 percent. In addition, ABCD modeled effective collaboration between Medicaid and other state agencies involved in children’s health and welfare.

“Everyone was stuck,” said child health policy expert Kay Johnson in a 2013 interview conducted for a history of Commonwealth Fund grantmaking in this field.

“Despite decades of trying, no one knew how to incorporate developmental screening for children into practice in a systematic, coordinated, cost-effective, evidence-based fashion. The [ABCD] program showed a way of doing it . . . one that didn’t take a lot of money or an act of Congress.”

Educating and Training Leaders in Minority Health

Meharry Medical College

In the 1960s, the financial future of Meharry Medical College — a private, historically black school founded in 1876 in Nashville, Tennessee — was in jeopardy. At that time, most African Americans had little access to white physicians or care networks, relying almost exclusively on black providers. Meharry was training half the nation’s African American doctors and dentists. But foundations that had long supported Meharry ceased operations, and the college’s alumni were unable to fill the gap on their own.

The Commonwealth Fund’s early support gave us a visibility which helped to attract other friends.

Under these circumstances, it would not have been unreasonable for Meharry to scale back operations. Instead, its leaders opted for a different approach: they implemented a comprehensive program for academic advancement. This entailed an expansion of graduate-level teaching in the medical sciences and a commitment to community medicine, with an emphasis on preventing disease and addressing the environmental and occupational hazards to good health. The Commonwealth Fund made a five-year grant to bolster these efforts.

Commonwealth Fund grantmakers understood that Meharry’s graduates played a crucial role in improving health services for poor and underserved African American communities, where severe inequities and discrimination compromised the ability to get quality medical care. As Lloyd C. Elam, Meharry’s president at the time, explained, “The Commonwealth Fund’s early support gave us a visibility which helped to attract other friends.”

According to a study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Meharry is today one of the nation’s top producers of primary care physicians.

The Commonwealth Fund Mongan Fellowship

In the mid-1990s, the Commonwealth Fund sought to further widen the circle of professional medical training to address racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Continuing a strategy that stretched back to 1947, when the foundation supported the National Medical Fellowships, the Fund in 1996 launched the Commonwealth Fund/Harvard University Fellowships in Minority Health Policy. Known today as the Commonwealth Fund Mongan Fellowship, this one-year, full-time, degree-granting program prepares physicians to lead the transformation of health care delivery systems serving low-income and minority communities into centers of excellence. Fellows undertake intensive study in health policy, public health, and management; participate in forums with national leaders in health care; and conduct practicum projects.

Of the 128 fellows who have completed the program, 60 percent have assumed senior leadership positions in federal, state, and local government; health care delivery systems; academic medicine; foundations; and nonprofit organizations. Noted Mongan Fellows have included Yvette Roubideaux, M.D., a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe of South Dakota and the first woman to head the Indian Health Service, and obstetrician/gynecologist Nawal Nour, M.D., a MacArthur Fellowship winner and founder of the first and only U.S. hospital center focused on the medical needs of African women who have undergone female circumcision.

“The fellowship was an incredible, transformative experience that changed my career trajectory forever,” said 1998 alumnus Joseph Betancourt, M.D., who today directs the Disparities Solutions Center at the Institute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Prior to the fellowship, I had little understanding of the inner working of leadership, minority health, and health policy. Afterward, I felt equipped to create a path focused on leading efforts to address racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care.”

Strengthening Health Care in Underserved Communities

A critical component of the health care safety net, community health centers serve millions of low-income Americans in medically underserved areas of the U.S. Many of these clinics lack the capacity to deliver the enhanced level of services many of their patients need.

The Safety Net Medical Home Initiative, sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund in collaboration with eight cofunders, was a five-year (2008−2013) demonstration project to help 65 community health centers in Colorado, Idaho, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Pennsylvania deliver well-coordinated services to patients through multidisciplinary teams of health professionals. Clinicians working within these patient-centered medical homes use decision-support tools, measure their performance, engage patients in their own care, and undertake quality improvement activities. Research has demonstrated that the medical home can improve quality of care, lower unnecessary use of services, and reduce the cost of care, especially for high-risk patients.

The primary care sites participating in the initiative and its learning collaboratives were a mix of rural and urban federally qualified health care centers, homeless clinics, residency training programs, and private practices that cared for some half a million patients. In addition to hands-on technical assistance, practices received funding for data infrastructure and training.

By the end of the demonstration, participating practices had made significant progress in implementing key elements of the medical home: more than 80 percent of the sites achieved recognition from accrediting organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance. The initiative also contributed to the transformation of primary care across the country. As of 2014, the resources it developed were being used by 14 primary care associations, seven academic health centers, the Indian Health Service and the Veteran’s Health Administration, several major health insurance plans, and some 500 federally qualified health centers.

“This was the first national demonstration seeking to accelerate transformation of the health care safety net through the medical home model,” said Melinda Abrams, the Commonwealth Fund’s vice president for delivery system reform. “Part of its success, I think, is that it made the case that robust primary care is the foundation for an effective and efficient health care system.”